THE GREAT JOE LOUIS BLUES by Augustine Himmel – The Milk House

THE GREAT JOE LOUIS BLUES

BROTHER, CAN YOU SPARE A DIME?

My grandfather always said the worst thing about the Depression was when a man got up in the morning, he had no place to go. That’s why he became a boxer. He figured if he didn’t have a job to occupy his time, he might as well spend a few hours each day working out in a gymnasium.

It was the autumn of 1990 and it had only been thirty hours since we lowered my grandfather into the nearly frozen ground of Munising, on the northern coast of Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, and that’s one reason I was trying to remember everything he’d ever told me about his boxing career. I wanted to recall each story, all the details, no matter how insignificant, in order to keep him alive in my memory.

With his old boxing gloves on the passenger seat of my car, I’d driven back home to Edson for the weekend, supposedly to study for my classes at Central Michigan University, where I’d be returning on Monday—my parents and sister were staying in the U.P. a while to help my dad’s mother—and what I remembered most vividly was my grandfather’s special technique for skipping rope, the only part of the sport he hated. He loved everything else about boxing: the fights under bright lights, the sparring, working on the speed bag, the heavy bag… even shadow boxing held a certain charm. I remember him saying, too, that the road work didn’t bother him. He would get up at five in the morning, put on the tennis shoes his manager had bought him, and then run out along Detroit’s waterfront where the homeless had built a shanty town. In the predawn haze he would see men warming themselves by fires they’d built in old garbage cans, some of them cooking coffee over the fluttering orange-and-red flames, and on his return run, as the sun began to rise over Henry Ford’s city, the men would be at the river’s edge where the fog hadn’t yet lifted, their fishing poles dangling over the steaming brown water, hoping a little luck would shine on them for at least one day.

My grandfather didn’t mind any of that. He approached his training methodically, thankful he had something to do—even more thankful his manager would feed him and thereby lessen the burden on his father, who’d been forced to sell his barber shop because so few people could afford a haircut. Later in the day, after calling on customers still able to pay their rent, my grandfather’s father would make the rounds of the shanty town, carrying nothing but a comb and scissors and large white towel, and he would try to sell haircuts to the homeless men for five cents apiece. The men would complain because he didn’t have his electric clippers with him, and how could they get a decent haircut that way? My grandfather’s father, weary from walking all day, would tell them they should be pleased, considering the price. He knew, however, that even five cents was too steep for men both Henry Ford and the government had deserted, and he would end up giving his services away for a penny per head. So my grandfather considered himself lucky to be boxing. But that rope skipping…

I never understood what he hated so much about the rope, only that he struggled with it, would not have done it if his manager hadn’t insisted. I was twelve years old when my grandfather showed me his special technique; at the time, he must have been in his early seventies. It was summer vacation and my sister and I were spending a couple of weeks in Munising. Grandfather decided I should learn how to box. “A boy needs to be able to protect himself,” he said. So he pulled his old equipment out of a cedar chest he kept in the spare bedroom, gloves and shoes and headgear, a mouthpiece, even his old trunks, and when he got to that rope he mumbled, “son of a bitch,” which made me giggle. Then, leaving everything except the rope, he said, “Come on, Blake. I want to show you something,” and we walked out to the garage, which at the moment didn’t have a car in it, because my sister and grandmother had gone grocery shopping.

While I waited, he stood in the middle of the garage in his T-shirt and blue jeans, frowning at the rope in his hands, as if it had done something wrong. Finally, he raised one eyebrow to me and said, “I always hated this rope, Blake, but I never let it get the better of me. And if you’re going to learn how to box, you might as well learn everything that goes along with it, even the rope skipping.”

Then he told me his secret for overcoming his hatred of the rope: He would sing while he skipped, and in that way divert his attention from the repugnant task. He always sang the same song, he said, one which not merely kept his mind occupied, but which also reminded him of how fortunate he was to be a good athlete, to have a manager who fed him chicken and steak when many people couldn’t afford a slice of bread. The song, born of the Depression, was called “Beans, Bacon, and Gravy.” [in the public domain]

Grandfather gripped the wooden handles at the ends of the rope. He stepped over the rope so that it rested in back of his heels. “I’ve forgotten most of the song,” he said, “but I think I can still do the refrain.” He paused, looked at me seriously and added, “Watch my feet. You don’t want to jump around like a wild man, make this any harder than it has to be.”

Then he started skipping rope, and though I dutifully watched his feet, which he barely lifted off the ground, landing alternately on the right and the left with a grace that surprised me, I couldn’t keep from glancing at my grandfather’s scowling face, at his thick, white mustache, as he sang the song from an era which, in my twelve-year-old ignorance, I knew almost nothing about:

Oh, those beans, bacon, and gravy,

They almost drive me crazy.

I eat them till I see them in my dreams.

When I wake up in the morning

And another day is dawning,

I know I’ll have another mess of beans.

He twirled the rope for at least five minutes straight—almost effortlessly, I initially thought—singing that refrain over and over. I desperately wanted to laugh, because I kept picturing all those hungry people, eating plate after plate of beans, and I was certain they must have farted up a storm, that Detroit must have shuddered from the force of so much flatulence; I imagined concrete cracking as during an earthquake, and scores of people, overcome by fumes, staggering the broken sidewalks like drunks. Yet I knew better than to laugh. I also knew, as the minutes passed, that my grandfather was working quite hard, because he started sweating, and that he disliked this particular work, because he began adding a word to the last line of the refrain, not so much singing the word as spitting it out of his mouth in disgust. He’d say:

Brother! I know I’ll have another mess of beans.

or

Sister! I know I’ll have another mess of beans.

And sometimes, with that blur of rope passing before his indignant face, he’d vary the remainder of the last line, too:

Mama! Please don’t give me no more beans!

or

Hoover! You ain’t worth a hill of beans!

When he finished, he handed me the rope, rested his hands on his knees, and in between deep breaths, he said, “Now, it’s your turn. Sing whatever you want. Or don’t sing at all. Just learn to move that rope.”

BAD BLOOD

The second reason I was thinking about my grandfather, trying to recall his stories that made vivid another era, was so I wouldn’t worry so much about my girlfriend, Emmylou, who was coming over with the results of her AIDS test. She had insisted on going alone to the health department in Flint while I was in Munising, and then later telling me what she learned. She said death was the most private of all things, and if hers was imminent, she wanted to find out by herself.

That’s just like Emmylou: Though we were only nineteen at the time, I sensed I’d never know another girl like her. She was the sole American Indian in Edson, a small town of Germans, Poles, and other European lineages, but her uniqueness went beyond her heritage. There was an ease about her, a tranquility not often found in people that age. Looking back, it seems she always wore the world like an old shirt.

Take, for instance, what happened when she told me she was going to have the test. We were alone in my parents’ house, sitting at the kitchen table, and Emmylou couldn’t have been calmer. She said she wasn’t really worried—she had none of those strange bruises you hear about, no lingering cough or loss of weight—but that lately she’d been thinking about the car accident she had with her adoptive mother in 1984, the summer before we started junior high, and the blood transfusion she received at the hospital. We weren’t close back then, so I hadn’t been aware she required a transfusion, only that she was pretty banged up, didn’t start school until the third week of September, and for a few Sundays hadn’t been with her parents at Trinity Methodist Church, which both our families attended. Emmylou said she wanted to ease her mind. She said worry could ravage a body as well as any disease.

“Tell me you’re joking,” I replied.

“I wish I could.”

“Please, Emm’.”

“There’s no punch line, Blake.”

“I can’t believe this is happening.”

Emmylou folded her hands on top of mine. “Don’t worry. I think they were testing the blood by then.”

“Were they?”

“I think so. I just want to make sure.”

I could tell she had doubts, and that really got to me, because 1984 sounded more like a borderline year, when the horror really started. I didn’t know when Ryan White, the hemophiliac, contracted AIDS from a transfusion, but remembered he had died the previous spring, a few months before his high school graduation—and ours. As we looked forward to getting our diplomas and moving on with our lives, the news of his tragic death was plastered all over the television like blood on the inside of an IV bag.

“But what if they weren’t testing?” I said.

“Even if they weren’t, I’m still probably okay. We’ll just have to wait and see.”

“But what if…”

Tears suddenly filled my eyes. Emmylou got up from her chair and sat on my lap and held me. I buried my face in her lovely Indian hair, trying to control my emotions.

When I lifted my head from her neck, she wiped the tears off my cheeks with her thumbs.

“It’s going to be all right,” she said.

Then she leaned over to kiss me, and in that brief second, I now believe, lurked the beginning of the end of our relationship: Instinctively I turned away.

Emmylou leapt off my lap and walked over by the refrigerator. She spun around, ran her hands through her hair and said, “I can’t believe you did that!”

“Emm’…” I pleaded, but couldn’t think of any way to defend myself. I felt like a coward. And the hurt in Emmylou’s eyes, which she had no way of hiding, hollowed me out like nothing I’d ever done before.

“You can’t get AIDS from kissing,” she said.

“I know,” I mumbled.

“Then why did you do that?”

“I don’t know.”

“You don’t know?”

“Well…” I said, and then blurted out what I must have been subconsciously thinking when I turned from her: “What if the government has been lying to us?”

“What are you talking about?” she said.

“You know how they say you can’t get AIDS from kissing, unless you’re really swapping spit, and you have a deep cut in your mouth, and then how the odds are still remote?”

“So? Have you been chewing razor blades lately?”

“So how do we know the government isn’t lying to us?”

“Why would they do that?”

“Maybe to keep the public from panicking, to keep the peace.”

“You’re getting paranoid, Blake.”

“And what does ‘remote’ mean? That’s a nice vague term to use when talking about life and death. Just how do they figure those odds?”

“Blake…” she said, shaking her head in amusement.

For a moment I became angry: “And you, more than anyone, should know not to trust the government. Look what they did to your ancestors—manifest destiny and all that crap, just so they could slaughter the buffalo and take all the land!”

“They slaughtered a lot of people, too, including women and children. Have you ever read Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee?”

“No.”

“Well, you should. Then you’d have a better idea of the evil that was done.”

I nodded.

“But the fact is, we’ve been lovers for almost a year, so a kiss is the last thing you should worry about.”

“I suppose…”

“And something else you should keep in mind: Even though I’m an Ottawa Indian, and proud of it, the people I’m closest to are right here in Edson. That’s where my family is… That’s where my paranoid boyfriend is.” She smiled, then slowly walked back over to me.

I looked up at her, amazed, and more than a little embarrassed. “I’m pretty stupid, eh?”

“No,” she said, resting her hands on my shoulders. “You have a right to be afraid. Everybody’s afraid. That’s why I’m having the test.”

OLD PUGILISTS AND QUICKSILVERED FISH

My grandfather boxed for three years after graduating from high school, one as an amateur and two as a professional. And though he started because he simply wanted to fill the long, listless hours brought on by the Depression, his manager had high hopes for his career. Fairly rapidly, my grandfather developed a reputation throughout Michigan as a solid middleweight. He fought all over the state. He took on anyone whom his manager, Duke—an old Italian so nicknamed because he loved listening to the Duke Ellington Orchestra—thought might improve his ranking, and thereby get both of them one step closer to the real money in boxing.

Eventually, however, they had to admit “solid” meant my grandfather had good technique, which he’d learned from Duke, that he had a boxer’s heart, which is courage on steroids, but that he lacked the menacing power and speed great boxers possess. Still, my grandfather never regretted his failure: It gave him something to do, it kept his belly full, and he stockpiled some wonderful memories. One time he met Joe Louis when the future heavyweight champion was training at the Detroit Amateur Club, and that, he often claimed, if nothing else, would have made the whole three years worthwhile.

As I turned his boxing gloves over in my hands and waited for Emmylou to arrive and tell me the results of her test, I recalled how my grandfather enjoyed talking about Joe Louis. He always called him the Great Joe Louis—never the Brown Bomber or simply Joe Louis. He said the boxer hadn’t been born who could have touched the Great Joe Louis in his prime.

Last winter, at the annual Shiver on the River walleye tournament, my grandfather bristled when I suggested Muhammad Ali, in his prime, could maybe have taken Louis. Ali had been retired for almost a decade, but I knew about his most famous fights by watching tapes of them on television. I also knew the mere mention of his name would elicit a strong response from my grandfather.

We were sitting on the frozen Saginaw River along with my father, inside my father’s shanty, not far from Veterans Memorial Park. My grandfather drove down from Munising each year to fish in the tournament, but he refused to eat anything that came out of the Saginaw River. He said the fish had been poisoned by runoff from Dow Chemical in Midland and Saginaw Steering Gear. Although this is true, the biggest culprits were the coal-burning power plants that had been around for a hundred years, because mercury occurs naturally in coal deposits and, when the coal is burned, mercury is released into the air and settles in the silt of lakes and rivers. And it stays there forever. Even Saginaw Bay had been contaminated. Pregnant women weren’t supposed to eat fish from the bay, which always made me wonder how safe it was for the rest of us.

“Nonsense!” said my grandfather, bent over his jig pole. “The Great Joe Louis would have buried Clay.” He still refused to call Ali by his Muslim name, believed his conversion was merely a ploy to stay out of the Vietnam War.

“Ali was fast,” I said.

“So was the Great Joe Louis!” he turned to me and snapped.

Because of the mild weather that day, it was comfortable inside the shanty. Grandfather had unzipped his coat, and I could smell the heavy wool vest he wore underneath. Our bait bucket was full of minnows we liked to attach to our Swedish Pimple lures.

“What about the Ali Shuffle?” I asked, unable to resist having a little fun. “Don’t you think Louis might have been caught off guard? Maybe Ali could have slipped in a jab while Louis tried to figure out what was going on.”

“Clay was a bum!” said my grandfather, his face reddening against his white hair and mustache. “A song-and-dance man. He should have been in vaudeville! The Great Joe Louis didn’t fool around in the ring. He was all business. That’s why he kept the championship for twelve straight years!”

“I always liked Gerry Cooney,” said my father, trying to lighten the mood.

“And I’ll tell you something else…” declared my grandfather. He raised one eyebrow like he always did when he wanted you to know he meant business. “The Great Joe Louis didn’t turn his back on his country. When Uncle Sam called him, he did his duty. He even put on exhibitions for the boys in the service. I shook hands with the man in Detroit, and I’m proud of it!”

Then he turned back to the fishing hole to signal the conversation was over. I didn’t bother mentioning that Muhammad Ali now lived in Berrien Springs, a sleepy Michigan town similar to Munising or Edson—his once-graceful body trembling from Parkinson’s, his speech embarrassingly slow from taking all those punches to the head—and that if my grandfather wanted to shake hands with him, he probably could.

“Scrape off those ice chips,” Grandfather said, changing the subject. “Those ones there, by the hole. If I do land one of them big, mutated bastards, I don’t want any ice chips catching my line.”

GENERATIONS

Emmylou asked me if I’d been chewing razor blades. It wasn’t a serious question, and I didn’t give her an answer. But as I sat in my parents’ living room waiting for her to bring me the results of her AIDS test, turning one and then the other of my grandfather’s boxing gloves over in my hands, it felt like I had swallowed an entire box; I could feel their sharp edges slicing away at the lining of my stomach.

I didn’t know what I would do if Emmylou had AIDS, other than get tested myself. The government said men rarely contracted AIDS from women, which didn’t comfort me at all. What troubled me most, however, was whether or not I would be of any comfort to Emmylou. I doubted I had the courage to watch her waste away, her death doled out in carefully measured increments of pain. And with that thought my shame nearly equaled my fear. I realized, sadly, you don’t simply inherit a boxer’s heart, but that it’s a requirement if love is to last.

How I waited… How I turned those gloves over and over… primitive gloves, filled with horsehair rather than foam. I rubbed my thumbs across the leather and the laces. I looked inside each glove, but didn’t feel worthy of putting them on. That day, I wished to have been born in a different time, when there was no such thing as AIDS, when lovers didn’t have to use condoms to keep from dying. Sure, Emmylou and I weren’t married, so technically we weren’t supposed to be having sex, but how practical is that when you’re nineteen years old and in love? It seemed the only thing religion did was prohibit one thing and another: “No” this, “No” that. And the people saying no, such as our Methodist pastor, Nora Lundstrom-Davis—my dad sometimes called her Pastor Hyphen when my mother wasn’t around—they were already married and having all the sex they wanted.

I suppose every generation has its albatross, and some of them had suffered terribly, like those generations of Native Americans who’d been hunted and forced from their land, but I couldn’t stop thinking about the burden mine was bearing. It felt as if we’d been singled out in a peculiar way. I thought maybe we were paying for the free love movement of the 1960s and ‘70s, “sins of the fathers,” as I’d heard Pastor Davis say in a sermon. Of course, that generation had the Vietnam War to contend with; I’m not sure being a young man in those days would have been so great, free love or not. And generations before them had to fear diseases like polio and tuberculosis, things I never had to worry about—although that autumn of 1990, doctors were speculating some bizarre strain of TB was emerging, caused, at least in part, by the AIDS virus.

Sitting there, waiting, I thought of the Depression my grandfather lived through, and how I’d never known the bitter taste of genuine hunger, how I’d never seen my father stagger home after working fifteen desperate hours, his feet aching, his face drawn with the long and unforgiving lines that come when a man doesn’t know if he’ll be able to feed his family. I thought of Joe Louis, who wore the uniform of a country that still denied him his civil rights. I remembered, too, seeing on television, old public service films of air raid drills, school children diving under their desks at the height of the Cold War in a futile attempt to survive a nuclear bomb. And yet, as awful as those times were, they seemed preferable to the thought of dying from making love—or from getting in a car wreck and having a pint of poison pumped into your veins. At least, in those times, the tender mercy of human contact was nothing to be feared.

When Emmylou finally arrived I put the boxing gloves down and went to the door to meet her. I watched her walk from her car in the waning evening light, her long black hair falling across her shoulders and nestling against her sweatshirt and the rise of her breasts. Though I was too nervous right then, just the sight of that straight Indian hair usually gave me a hard-on. Sometimes, when we made love, Emmylou would sit on top of me. I relished looking up at her hair, how it shined against her caramel skin, the way it parted for the hard brown nipples on her soft, nodding breasts. And when Emmylou leaned over me, her hair falling around my head and curling itself on the pillow, it was like she’d built our own little world with just the cover of her hair; I wouldn’t see anything but Emmylou and I wouldn’t feel anything but the smooth, rhythmic motion of our bodies. Afterwards, I’d sometimes be sad in the midst of my joy: It was difficult to believe I was Emmylou’s true love.

“Kiss me,” she said, when she stepped inside the door.

“You mean?”

“I’m clean,” she said, as if referring to a load of laundry.

“Emm’,” I sighed, so relieved my knees almost buckled. I took her in my arms and buried my face in her hair. And while outwardly she appeared nonchalant, I felt something more in the way she hugged me, an extra little squeeze that betrayed her own sense of relief.

“What about that kiss?” she finally said.

So I kissed her, relishing the familiar taste of her mouth, the playful movement of her tongue across mine, and the peace that comes from holding someone you love and knowing that, at least for the moment, you’re both healthy and safe and free to enjoy the miracle of each other. We stood by the door and kissed until our mouths tired, and then went into my bedroom.

Afterwards, we lay facing each other and talked. Emmylou said one of the worst things about having the test was keeping it a secret from her parents. She didn’t want to worry them—they were overprotective because they couldn’t have children of their own, and Emmylou was the only one they had adopted—but as she waited for the results, and with me away at my grandfather’s funeral, she started feeling guilty for not telling them.

“It worked out for the best,” I said.

“You’re right… The waiting was just more difficult than I thought it would be. And I wished I could have been in Munising with you.”

“I know,” I said, twirling the lovely hair resting against her collarbone.

“How’s your grandmother?”

“I think she’ll be okay—after a while. They were married for over fifty years.”

“Yeah… That’s some kind of love, isn’t it?” Emmylou smiled at me, but I could have sworn I saw a touch of sadness behind her smile, and that triggered a sadness of my own, the kind where lying in bed next to Emm’ just seems too good to be true.

“Hold me,” she said.

Emmylou didn’t spend the night. Because it was Friday, she could have told her parents she was staying at a girlfriend’s, but she didn’t want to be dishonest after having kept the AIDS test a secret from them. I said I understood. Although I cherished the rare occasions we would actually sleep together, such as during an all-night party, when someone else’s parents were out of town, I was, to my surprise, content to see her go. I think both of us were more alone than we wanted to admit to ourselves.

So I stayed up most of the night, sitting on the sofa, drinking bottles of Michelob and staring out the darkened living room window. Now and then a car or truck would go by, the hazy glow from its headlights visible before the vehicle appeared on the street in front of our house. Sometimes I tried to guess the exact moment the vehicle would arrive, but with little success. All I knew was that after the glow, it eventually came. There was no stopping it. There was no stopping anything, no matter how hard you tried.

Near morning I finished the last of the beer and staggered back to bed. I fell asleep and dreamed I had ringside seats in a sold-out coliseum, my beautiful Emmylou was there next to me, and my grandfather, though outweighed by at least forty pounds, was young and strong and working his way around the canvas, making the most of his good technique and his boxer’s heart, battling the Great Joe Louis for the Heavyweight Championship of the World.

*

Learn more about Augustine on the Contributors’ page.

An additional story by Augustine, Lady of Sorrows, was published by The Write Launch and is available here.

(Photo: National Museum of American History Smithsonian Institution/flickr.com/ CC BY 2.0)

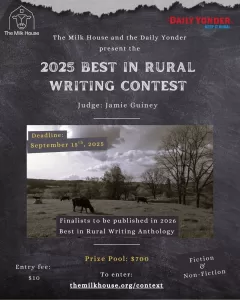

The 2025 Best in Rural Writing Contest is now underway!

$500 first prize, $200 runner-up. $10 entry fee. Finalists will be published in the 2026 Best in Rural Writing print anthology.

Accepting fiction and nonfiction under 7,000 words. To enter, click here.

Deadline: September 15th, 2025

The 2025 Best in Rural Writing Contest is sponsored by The Daily Yonder. The Daily Yonder offers news, analysis and stories from Rural America, free for readers to enjoy. Visit dailyyonder.com to get more great rural stories, or sign up to their newsletter to receive rural reporting directly in your inbox. Alternatively, you can listen and subscribe to their podcast, Rural Remix, wherever you get your podcasts.