The Escapee’s Lover by Dennis McFadden – The Milk House

Seems like every time you turn around, they’re carting somebody else out to die. Somebody takes a stroke or a heart attack, they carry them on up to the hospital to die, or over next door to the Memorial Home. As a general rule, they don’t like anybody dying here. Me, I’m planning on getting out of here on my own two feet.

They call this place the Darius Litch House, not Home, which ought to give you a clue right there. It’s over a hundred years old, and you could sail a kite in the drafts from the windows. They really knew how to waste space back in them days. There’s new carpets laid down all over the place, nice and thick, so your hip won’t bust so easy when you trip over your shoelace, and we got a piano up in the parlor and a TV in every room—regular lap of luxury. Even got a bunch of birds in cages and our own damn cat. I always been a dog man. For years I seen the place every day when I delivered beer across the street—used to have my own distributorship, but I wound up drinking more than what I sold. If you’d told me I was going to end up here myself, I’d of said you were crazier than all the old coots in it.

I’d only been in a few weeks when Missy busted me out. I’d already busted out a few times on my own, I don’t recall how many. What I do recall is I was setting there planning my next one, setting down there at the end of the hallway, near the door. Of course they were on to me by then and had Elroy, the janitor, keeping an eye on me. Elroy’s big as an outhouse, but not near as smart. One time they told him to feed the birds and let out the cat, but he fed the cat and let out the birds. Must not of fed the cat enough, though, cause then she ate two of the birds.

Ruthie wandered down the hall to where me and Elroy was setting staring one another down. All Ruthie ever does is sleep and wander, wander and sleep. She’s the judge’s widow. Missy’s her kid, hers and the judge’s. Ruthie’s got yellow hair, and she don’t look half bad if you squint your eyes to look at her. Ruthie says, “Aren’t they going to feed us?”

I said, “It ain’t suppertime yet.”

That didn’t make a dent. “They have to feed us sometime,” she said.

“They just fed us.”

She stood there with her chin up. Her hands was working. It was like she was knitting, but there wasn’t any knitting needles in her hands. “We are supposed to have regular, nutritious meals. That is what we are paying for.”

“They just fed us our lunch,” I said. “We had hamburgs.”

Ruthie looked down her nose at me. There’s a haze in her eyes, like little clouds. “Those were not hamburgs,” she says. “Those were meat patties.”

You can’t leave. If you just sashay on out the door, the alarm goes off, and they just come out and grab you in the parking lot—I ain’t as quick as I used to be. There’s this keypad contraption by the door and if you punch in the right numbers the alarm don’t go off when you open it up. But nobody’ll tell you what the right numbers are to punch in. I was setting there watching for somebody else to leave, figuring I could slip out then. But Elroy was setting there watching me watching.

Brenda the fat nurse comes wheeling her cart down the hall. “Chester,” she says, “what are we doing?”

“I don’t know about you,” I said, “but I’m setting here minding my own business. You oughta give it a try sometime.”

“Aren’t we forgetting something?” I checked my fly—it was up. My shirt was buttoned, more or less, my shoes were tied, and I had at least two socks on. Brenda said, “We know we’re not supposed to take our picture out of our room.”

I clamped my arm down over it. “It’s my wife’s picture.”

“We could fall and break the glass and cut ourselves.”

“Or we could go peddle our pills someplace else.”

“Do you want to give it to me, or do you want Elroy to take it?”

“Neither!”

Elroy grabbed the picture, and lifted me clean up out of the chair with it. That’s when Missy comes in, just as we were tussling for it. Wasn’t much of a tussle. Missy had her sunglasses on, and she smiled like she walked in on a tussle every day, like we were putting on a show just for her. Then she looks over top of her sunglasses at my picture Elroy had grabbed. “What a pretty girl,” she says.

Brenda shakes her head and clucks her teeth, and says, “Chester, you better start behaving yourself if you want to stay here.”

“I don’t want to stay here!”

Brenda smiled. “Where you gonna go to?”

Ruthie was wandering around up at the other end of the hallway, where the couches are at. When she saw Missy she came down and went to give her kisses, but she missed. It put me in mind of a fish trying to breathe. Then Missy took Ruthie by the hand and led her back up the hallway toward her room, and Missy looked back over her shoulder at me. I didn’t remember the last time a woman looked at me like that, and it took me back, way back, to some place I couldn’t quite get to because it stopped just before I got there.

There was maybe twenty old women in the Darius Litch House, me and old Yeaney. Me and Yeaney as a matter of fact were the only two in the whole place that had balls. Why is it women live so much longer than men? I got my own theory. We spend all our lives pumping them full, they spend all theirs draining us dry. Simple as that. In the long run, it’s bound to tell.

Old Yeaney must have been damn near a hundred. He just set up there all day long on the couch in the hallway with his cane poking up between his legs, his hands resting on top of it like it was his pecker. He hadn’t said nothing all day long. Hell, I seen him go a week without saying nothing. You wouldn’t know if he was alive or dead. Then all of a sudden he looks up and says, “Ice cream and cookies—that’s what I need!”

Damned if Brenda doesn’t go and get him some ice cream and cookies.

There’s two of them little couches up in the hallway there—loveseats, they call them—right where the stairs come down and another hall heads up the other way. Everybody likes to set out there on the couches instead of in the parlor right around the corner where the piano and the birds are at. They’re afraid they’ll miss something if they ain’t out there in the hallway. And if they’re missing something, they figure they might as well already be dead.

Two old women, Hazel and Alverta, were setting on the couch next to Yeaney where they usually sat. Hazel was skinny and white, except for her eyes, which was red and hard. Alverta was all fat and saggy, and her hair looked like worn-out porcupine quills.

Missy and Ruthie come walking up the hall. Hazel said, “Who are you?”

“Why that’s Ruthie’s daughter,” Alverta said.

“No it ain’t,” Hazel said.

Missy just smiled. She still had her sunglasses on.

Just then Yeaney starts hacking up a storm. Yeaney had black lung. When he got to hacking good, he sounded like he was trying to cough one up. “Yeaney, please,” Hazel said, “we got company.” So Yeaney quit coughing. Then he leans over on one cheek and cuts one loose. Never even bats an eye.

“Why does he lean over on one buttock like that?” Ruthie said.

“So he don’t shoot straight up in the air,” Alverta said, and Hazel come out with a red-eyed cackle.

Ruthie said, “Is he eating ice cream and cookies?” She couldn’t believe it.

Missy said, “Mother. I think The Price is Right is on.”

“Wonderful,” Ruthie said.

For a little while there, everything seemed to stand still. Missy and Ruthie up at the end of the hallway just out of one another’s reach, Yeaney and the old women setting on their loveseats. Maybe the word wonderful was what done it. The sun was shining in on my cheek through the glass up over the door, and then I seen the cat asleep on the windowsill by the green plant. I smelled something that smelled like raw potatoes, and it put me in mind of my Helen fixing supper and how the knife used to click on the kitchen counter, and how the onions used to sizzle in the frying pan. That lasted maybe an hour, and then Missy comes walking down the hall toward me all by herself. She punched the number in, and opened the door. Then she stands there holding the door open, staring back at me over top of her sunglasses. “Well?” she says.

Elroy’s chair was empty. I said, “Hold on a minute.”

“Don’t forget your picture,” she said.

I said, “That’s what I’m going for.” Elroy was up on the stepladder changing a light bulb. He never even seen me. He was trying to figure out which way to twist the bulb.

Missy used to wreck cars. That’s about the extent of my recollection of her. She used to hang around the bars when she first got to drinking age, but I hadn’t seen her in years, till she come in one day to visit Ruthie. I remember one car, a green Mercury, she rolled it over so hard the jack was sticking straight up through the trunk lid like an arrow somebody shot through it. But she never killed nobody, and her old man was the judge, so nothing much ever come of it. Then she got married and moved off.

She said, “You’re Chester Emerick, aren’t you? Chet. I remember you. You used to deliver beer.” Her voice was kind of deep, like an echo out of a well. She took off her sunglasses and cleaned them with the hem of her skirt, which was red. Her eyes was all puffy.

I said, “How come your folks named you Missy? Didn’t they think you was ever going to grow up?”

“No, and they were right. Hop in.” It was a little red car with bucket seats I wasn’t sure I’d be able to climb out of. But I didn’t have no place else to go. “This thing got safety belts?”

She laughed. “I’m all grown up now, Chet. I haven’t wrecked a car in probably a week.”

“How about I buy you a drink?”

“You sweet-talker.” She nodded across the street toward the Pub Bar. “Over there?”

“They don’t serve me over there. Last time they just called them up on the phone to come over and get me.”

“How about the Green Lantern?”

“They don’t serve me in there either.”

“The Golden Bull?”

“Nope.”

“You still barred from Jum’s too?”

I just looked at her. I couldn’t remember. I drew a blank on Jum’s. She had a little grin. I wasn’t sure there was anyplace in town that was going to serve me any more. “I’m just teasing you, Chet,” she said. “Jum’s has been closed for years.”

“I ain’t got any money on me,” I said.

“My treat. How about the Holiday Inn?”

It was out by the Interstate. “That sounds good. That oughta do just fine.”

They wouldn’t serve me there either. They had my picture taped up by the cash register next to a bunch of bounced checks. Missy said, “I know a place,” and she took me for a ride.

She must’ve been going a hundred. I kept a hold of my picture. Kept it face down on my lap. We’d crest a hill and glide down and then up again, and from up on top you could see pastures and farms and woods, all laid out for miles around in the sun. I felt like I was flying. I felt like I could whip Elroy. Some noise was on the radio, and what with that and the wind in my ears, I didn’t have to try to think any. I didn’t know where I was, or where we were going to, but I’d been there before, so it felt like going home. Missy turned down the radio, reached over and tapped my picture. “Is that your little girl?”

“That’s my old lady. Helen.”

“You know, they have wallet-sized pictures. Pictures that fit in your wallet.”

“I ain’t got a wallet.”

“So how come you lug it around like that?”

I lied. “Just to piss ’em off.”

“You sure it isn’t your little girl? She looks awful young.”

“Well she ain’t awful young. She’s dead.”

“Who? Your wife or your little girl?”

I had to think. “Yep.”

“I’m sorry.”

“You just get to where you’re sick and tired of it all.”

“Yes, you do,” Missy said. We swooped down around a banked curve and swooped back out again, but my stomach kept heading out toward a big silo in the field. We come on this big old Buick doing about thirty, and Missy slammed on the brakes, honked her horn and zipped around it. There was an old woman driving it. She bowed her head at us like we were on a mission from the Government.

“So how’s my mom doing?” Missy said. “Ruthie.”

“Ruthie? She’s a bubble or two off plumb.”

“Do you think she’s happy?”

“Hell no, I don’t think she’s happy. Happy?”

She smiled. I wasn’t expecting that. “You reap what you sow, Chet. What goes around comes around—kind of like a boomerang, don’t you think?”

My brain was beginning to itch. “If you say so.”

“Sometimes I go into the Darius Litch House, and I don’t even go to her room. Did you ever notice that? I go up and sit in the parlor all by myself, just to listen to the birds.” She looked over at me, and I pointed toward the road. “And there’s poor mommy just down the hallway waiting for me, wondering where in the world I could be.”

I took my eyes off the road long enough to look at her.

“Oh, dear, what can the matter be?” Missy sang with a little grin, “oh, dear, what can the matter be?” I pointed toward the road.

She said she lived in Grayville. Or Grave Hill. I ain’t sure which. She pulled up in the parking lot of some motor lodge place, and in we went. It was a lounge, not a bar. As a general rule, I don’t like lounges, but the beer was cold, and you can’t ruin a good shot of Seven. She started in on the Margaritas. The bartender was some kid in a yellow vest who kept looking at us like we just climbed out of a flying saucer. He was as good as invisible to Missy. She played some country tunes on the juke box, and told him to crank it up. She lit up a smoke and looked like she could of lived there, perched up on the barstool with her legs crossed and her skirt hiked up. Legs weren’t half bad, either.

I couldn’t get a fix on the room. There was walls of mirrors in front of other mirrors, and walls made out of glass bricks, and black walls with little spots of colored lights, and half walls, and walls every which way. All kinds of angles and steps and levels. One big wall of windows with red curtains that were glowing from the sun outside. I had to grab a hold of the bar to keep from sliding off.

I got hungry. They didn’t have any pigs’ knuckles or pickled eggs. Damned lounges. Kid give us a bowl of goldfish, little crackers. Turned my fingers yellow. Missy didn’t eat any. She said she hardly ever ate, and she was skinny enough I believed her. The opposite of Ruthie, always worrying where her next meal’s coming from.

So we drank to Ruthie. We drank to Missy’s three husbands she told me she’d been through one at a time. We drank to Helen, and we drank to cancer. She didn’t want to drink to the judge. She said, “Fuck the judge,” then she giggled and said, “Pardon my French.” She told me now that I’d got old, I reminded her of the judge. She called me the poor man’s Herman Foulkrod. That was the judge’s name. So we drank to poor men, then we drank to sons you ain’t heard from in years, and to little girls who grow up into fat women and move down to Florida. She said she didn’t have no kids to drink to. So we drank to grandsons who rob all your money, and stick you up in the Darius Litch House. She was doing shots and beers by now too. She kept buying, I kept drinking. I recall when I used to keep buying, to keep the women drinking. I figured she was out to get me drunk.

It worked. Willie Nelson come on singing a song I remembered was one I used to like, and so I told her I loved her.

“You sweet-talking son of a bitch,” she said.

I said, “You’re the only woman for me.”

“Stop it Chester, or I’m gonna get naked right here.”

“Me too.”

She took a puff, and the end of her cigarette lit up. “How long’s it been since you got laid, you old coot?”

I said, “What time is it now?”

I really did love her. It had crossed my mind that I might never get drunk again, and while I know good and well that drinking’s the source of all my misery, I know even better it’s my only source of comfort. Missy was my goddam Florence Nightingale. There was little drops of sweat on her forehead. I never looked at her face before. There was a little drop of sweat in the corner of her eye. Her make-up was too thick and starting to crack, and her eyes were all black like the wall with the little colored lights.

“Let’s dance,” she said. “Here, Helen can’t see us,” and she put her picture face down on the bar. We danced some, but I don’t move around so good anymore. Helen didn’t miss nothing.

I must’ve rested my eyes. I remember hearing voices in the dark. It was happy hour by then, and the noise was louder when your eyes were closed. I guess it’s true blind people hear better than we do. I could hear every ice cube clink and every Zippo click and every ashtray sliding on the bar and every beer pop open and the gurgle of every pour. Somebody said, Who are you? and I heard Missy say, I’m daddy’s little girl, and there was laughing and chattering and people all talking at the same time. Somebody said, What do you do? and Missy said, Margaritas mostly, a CC-water-back now and then, and every so often a shot of Jim Beam. You name it. Then I heard more. I heard plenty. I heard Yeaney hacking up a storm and the old hens clucking and the alarm whining at the Darius Litch House and Helen crying and my old man saying the Lord’s Prayer. I heard Missy laughing like a crazy woman on top of the pool table in Jum’s that’s been closed now for years. Pool balls clacking and glass breaking. I heard the bell bonging twelve o’clock from the Court House tower and I heard the police siren and the crack of my granddaddy’s rifle and a deer tumbling through the brush. I heard rain falling on the tin roof of the shed right outside my bedroom window after Helen wasn’t there to hear it no more. I heard the wind blowing and the sun shining. Then I heard the kid in the yellow vest saying, I think you and your father have had enough, and I heard Missy call him a snot-nosed little shit.

She was pulling me up out of the car in some strange place. It was a field of some kind. The air cleaned out my head, right through my nose and out my ears. There was a few trees throwing long shadows across the way. And there was fog, little puddles of it laying down on the ground. I said, “Ain’t this fog upside down?” I couldn’t find my feet.

Missy said, “You must have to pee. You haven’t peed in a long time.”

I started crying. I couldn’t help it. Nobody ever cared if I peed before. I said, “I do.”

“Over this way,” Missy said.

I stepped on something hard. “What’s this?”

“That’s one of the markers. They have them flat so they can mow.”

I kicked the fog away. It said George Allshouse 1916 – 1981. “We in Grave Hill?”

“No. This is the cemetery.”

Across a little rise I made out a statue of two big hands holding a book open. Must’ve been the Bible, I figured. They were tucked in a nest of spruce trees. Biggest hands I ever seen. Down the other way I made out a mound of rocks with golden letters on it that said Babyland. “Says over there we’re in Babyland.”

“That’s the part of the cemetery where they bury babies,” she said. “They bury babies for free, in hopes their parents’ll buy a plot then.”

“That’s a pretty good deal,” I said.

“Are you crying, Chet?”

“No, I ain’t crying.”

“You are too. How come?”

I lied. “All them dead babies.”

“You’ll feel better after you pee,” she said, and I started crying even more.

Missy hiked her skirt up, tugged her underpants down – they was red too – and squatted down to pee. “Why, you’re pissing on somebody’s grave, ain’t you?” I said, wiping my eyes. I listened to the splash.

She didn’t say anything right away. She really had to pee. She must’ve been saving it up. Finally she let out a little sigh and said, “The judge’s. I bring all my boyfriends here to pee.”

I walked over for a look. Sure enough: The Honorable Herman Morris Foulkrod 1900 – 1975. If I’d of been thinking, I’d of wondered why Missy would want to go and piss on her old man’s grave, but I wasn’t. He was sheriff before he was judge, and he’d threw me in jail a couple times, so I kind of took to the idea of pissing on his grave.

“How about your husbands?”

“Them too. In fact I brought my whole group out here one time to pee on his grave.”

“A whole group?” I said. She’d stood up again by now. “All at the same time?”

“Yeah. It was kind of crazy.” She looked down to admire her little puddle in the fog. “Well hurry up.”

“I can’t with you watching me.”

“I’ll walk over here,” she said.

“I got one of them bashful bladders.”

“I’ll take a stroll through Babyland.”

I listened to her strolling away, whistling She’ll Be Coming ’Round the Mountain. The fog was up to my knees. I was sinking in it. I closed my eyes to concentrate, and started swaying. I really wanted to piss on the judge’s grave in the worst way and make Missy proud of me. I thought about heavy rain and tinkling brooks and raging rivers, and imagined Niagara Falls beating down all around my head. I imagined the fog coming up all around me, and those big stone hands lifting me up like a dandelion out of the yard, and big stone lips blowing me away like fluff flying out across the twilight.

“I love you, Sweetie.” It was Missy. Woke me up. We were in her car, and it was dark outside. I said, “I love you too, Sweetie.”

Missy said, “I miss you so much.” She was crying.

Then I seen she wasn’t talking to me. She was turned away from where I was setting, toward the window on the driver’s side. Then I seen she had one of them mobile telephone contraptions. It was foggy outside. There was this row of bright lights in the dark, big glowing balls going smaller out away into nothing.

She quit talking, and I said, “Who was that?”

Missy sniffed, and wiped at her cheek. “That was my little girl. Katie.”

“Thought you said you didn’t have no kids.”

“I lied. Katie lives with her father in Virginia. God only knows what he’s doing to her.”

She didn’t say nothing else. I said, “Where we at?”

“I have to go back to Grayville.” Or Grave Hill.

“My legs is kinda chilly.”

“You took your pants off.”

I couldn’t remember taking them off, but I figured I must’ve had a good reason, so I didn’t say nothing. The row of lights wasn’t throwing any our way, and I couldn’t see much. She was beside me like a shadow. She wiped her eyes again, and pressed at her cheeks like she was putting on a new face. The fog was white around the lights, and I was wondering how far away they went when I seen a red one floating in toward us, and I heard this roar commencing that got so loud I could feel it in my chest. And I was just about to figure out that we were at the county airport when Missy reached over and cupped her hand around my privates. It was like she put them in an oven. I started feeling toasty all over.

She whispered in my ear. “Does that feel good, Chet? Do you like that?” Her voice was way down at the bottom of the well. Like someplace where it shouldn’t have been.

“Don’t feel too bad,” I said.

“Did you make your little girl do this?”

I didn’t know what she meant.

“Did you?” She started squeezing.

“Can I have my pants back now?”

“Did you have your pants on when you slipped down the hallway, Chet?” She squeezed harder. “While Helen was sleeping? Or pretending to?”

“What hallway’s that?”

She gave a real hard squeeze that bounced me up on my best behavior. “The hallway to your little girl’s room, Chet. That hallway.”

They say your life passes before your eyes. A little bit of mine did. Quite a bit, I guess, considering the big chunks of it that are already AWOL. There was a lot of backseats and alleys and cheap motels and women that wasn’t my Helen. There was a big cloud of smoke and the smell of booze, and foggy barroom lights, and my ma standing next to the old man’s grave trying to hide her cigarette behind her dress. I was scared. I didn’t know what to say. It just came out. “I ain’t the poor man’s Herman Foulkrod,” I said.

She turned loose of my privates. She started crying again. She buried her face in my shirt, and just set there sobbing. “I know,” she said. “He’s dead. The son of a bitch.”

We sat there for a little while. Missy was shivering. She was just a little girl.

I put my arms around her, kept her warm. I said, “This here’s been the best day of my life.”

I watched the lights of the planes roaring in and out, and figured Missy was on one of them. After a while, I seen a little light come bouncing out toward me through the fog. This guy with an Avis hat come out to check for gas and mileage, and see if there was any dents or scratches on his car. Must’ve knew how Missy drove. When he seen me, he jumped back, startled. He shined his light in on me. “What are you doing in there?”

I shrugged. “Just setting.”

“Where the hell’s your pants?”

I just shrugged again.

Old Yeaney up and died about a month later. They’d let me back in the Darius Litch House, and I’d been figuring I wasn’t going to be busting out again. Least that’s what I figured at first. But by the time old Yeaney died, my mind was starting to waffle on it. Matter of fact, I was setting back down there at the end of the hallway, watching the door.

Missy hadn’t been back to visit Ruthie since the day she busted me out and left me without any pants. Took some time till that sank all the way into my brain. Figured for a while there she must’ve just been drunk or crazy or both. But then I was setting there in the corner with the cat on my lap one day, watching Hazel and Alverta squabbling over their Scrabble game, when it come to me like one of them light bulbs going off over your head in a cartoon. It was clear as a bell to me what had happened. I seen him there, the judge, naked and sweaty underneath his long, black robe, slinking down a long, black hallway, slinking straight down towards hell.

Ruthie come wandering toward me. Now I knew why she spent her days wandering down hallways. She didn’t say nothing to me, just looked at me and sniffed like she could smell something bad, then turned around and moseyed on up past Hazel and Alverta. She set down next to Yeaney on the other loveseat. Yeaney was already dead, but nobody knew it. He set there dead for the better part of the day, and nobody knew it.

Ruthie started talking to him. Everybody was used to him setting there asleep, so nobody give it much thought. He was setting there like he always was, with his hands on his cane. Ruthie asked him when they were going to feed us, but of course Yeaney, being dead, didn’t have much to say.

Alverta said, “Somebody stinks.” Hazel scrunched her red eyes up, and sniffed.

Ruthie looked at them, and Alverta said, “Better not sit there, Ruthie. I think Yeaney pooped his pants again.”

Hazel says, “Abandon ship!”

Brenda the fat nurse come out of a room across the hall and says, “Yeaney, did you have another accident? Yeaney?”

She reached down and shook his shoulder to wake him up, and knew right away he was dead. She says, “Oh no,” and called the head nurse who called the supervisor, and pretty soon the whole hallway filled up. A couple nurses from over at the Memorial Home come running in and scared the cat, who raced off. The birds up in the parlor started squawking and carrying on. Ruthie couldn’t figure out what all the fuss was about, why everybody was standing around gawking at her and Yeaney.

Brenda said, “Ruthie, get up. Get up, Ruthie. Yeaney’s passed on.”

Ruthie was in a snit cause she had to get up. She didn’t like all the commotion. She wandered toward me, back at the end of the crowd. I was the only man in the place now, at least the only one still breathing.

Ruthie says, “Does this mean they’re not going to feed us?”

I said, “Yep. Sure looks that way.”

She looks at me like somebody just tore her heart out.

I said, “Tell you what, Ruthie old girl. I’ll go out and pick us a mess of sprouts and greens and you can fry ‘em up in your frying pan.” She didn’t like that idea. She looked down her nose at me, from behind them little clouds in her eyes.

*

Learn more about Dennis on the Contributors’ page.

Learn more about Dennis on the Contributors’ page.

Dennis’s latest novel, Old Grimes is Dead, was published in 2022 and is available here.

(Photo: ShotsAtRandom/flickr.com/ CC BY 2.0)

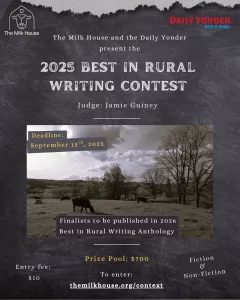

The 2025 Best in Rural Writing Contest is now underway!

$500 first prize, $200 runner-up. $10 entry fee. Finalists will be published in the 2026 Best in Rural Writing print anthology.

Accepting fiction and nonfiction under 7,000 words. To enter, click here.

Deadline: September 15th, 2025

The 2025 Best in Rural Writing Contest is sponsored by The Daily Yonder. The Daily Yonder offers news, analysis and stories from Rural America, free for readers to enjoy. Visit dailyyonder.com to get more great rural stories, or sign up to their newsletter to receive rural reporting directly in your inbox. Alternatively, you can listen and subscribe to their podcast, Rural Remix, wherever you get your podcasts.