Linebreeding And Inbreeding: What Is The Difference?

Linebreeding can be thought of as inbreeding with a purpose, where the purpose is to increase the genetic relationship to an outstanding individual while at the same time avoiding the accumulation of additional inbreeding to less worthy ancestors.

By Prof. Michiel M. Scholtz and Mike D. MacNeil of ARC-Animal Production, Irene, South Africa; and Delta G, Miles City, Montana, United States

In the normal course of a breeding programme in which the mating of close relatives is avoided, the combination of genes that gave rise to the outstanding individual is continually diluted over time. Thus, after the passing of a relative few generations, the combination of genes that gave rise to an outstanding individual is in all probability lost forever. Linebreeding is the tool in a breeder’s toolkit that can be used to prevent this loss. In linebreeding the goal is to increase the genetic relationship to the outstanding individual while at the same time avoiding the accumulation of additional inbreeding to less worthy ancestors.

When linebreeding is practised, it is important to do performance recording for traits such as birth weight, weaning weight, cow weight and fertility (inter-calving period). If this information is available, it will be possible to evaluate the effect of linebreeding on these traits over time.

Inbreeding results from the mating of related animals. Everyone realises that the mating of a father with his daughter or the mating of a brother and sister definitely produces inbreeding. But what about the mating of a grandfather with his granddaughter, a nephew with his niece or two cousins – is that inbreeding? In humans, this is commonly regarded as inbreeding and is normally forbidden.

The primary effect of inbreeding is that it increases the chance that an animal will receive the same allele of a gene from both parents. This will reduce the degree of heterozygosity in the population and increase the relationships between animals to more than 50%. Inbreeding will therefore lead to an increase in homozygosity, which is the easiest way to fix certain alleles in the population. This will lead to uniformity, but it also increases the chances to fix undesirable genes, such as a skew face, hypoplasia and laminitis. However, this was the basis on which inbreeding was used in the formation of many breeds in the past.

Inbreeding depression is the reduction in the performance of inbred animals. This reduction is more subtle and more important than the occurrence of adverse recessive traits that are influenced by few genes and are usually associated with inbreeding. It is known that inbred animals do not adapt as well to changing conditions, and their reproduction and production are also likely to be lower, compared with contemporary animals that are not inbred. Inbreeding should thus be avoided, unless it is done with a specific aim in mind.

The Principles Of Inbreeding And Relationship

To be successful in a linebreeding programme, a breeder must also understand the principles of inbreeding and relationship. Of primary importance in a linebreeding programme is the selection of the “outstanding” individual that will serve as its foundation. Finally, success in a linebreeding programme also entails patience, persistence and good luck.

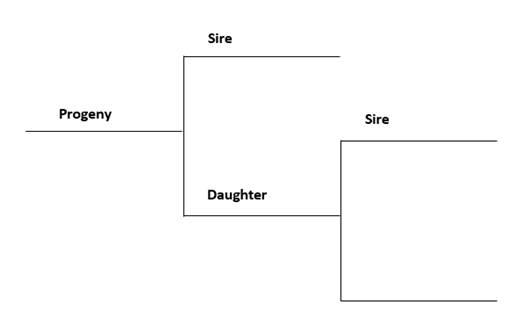

The pedigree diagram in Figure 1 illustrates the mating of a sire to one of his daughters. Numerically, the relationship of the sire to his daughter is 0.50. The relationship of the sire to the progeny is 0.75, and the inbreeding of the progeny is 0.25, which is one-half the relationship of the progeny’s parents.

Figure 1

Increased Risk Of Failure

It should be recognised that linebreeding also increases risk of failure in the breeding programme. This risk is present because the chosen outstanding individual might also be a carrier of a recessive allele that is undesirable. The inbreeding that accompanies any linebreeding programme might also yield inefficiencies in production that prove to be too costly. As a rule of thumb, the outstanding individual that is chosen as the basis of a linebreeding programme should be a truly elite individual within its breed.

A successful linebreeding programme requires patience and persistence, as it entail several generations of breeding. With a nine-month gestation period, being able to first bear offspring at two to three years of age, and producing fewer than one offspring per female per year, cattle have a long generation interval. Modern assisted reproduction technologies such as artificial insemination, embryo transfer and juvenile follicle aspiration may hasten the programme along somewhat. However, breeders considering a linebreeding programme would be well advised to think in terms of at least a 10-year planning horizon.

When related individuals are mated, as in a linebreeding programme, their progeny are expected to have alleles that are identical for more genes than if the parents were not related. If inbreeding and relationships are intertwined, why is inbreeding to be avoided when a degree of relationship is desired? Alleles with detrimental effects tend to be masked by an alternative allele of the same gene (in other words, the detrimental alleles tend to be recessive). Thus, the detrimental alleles only become apparent when they are identical on both chromosomes.

Relationship Coefficients For Prospective Mating

In South Africa, there are a few breeds where there is a lack of good-quality unrelated breeding bulls. In this situation it is important to take note of the relationship coefficients for prospective mating. There are computer programs that will alert the breeder if a certain mating will result in a level of inbreeding that is generally unacceptable. These programs may be less useful in a linebreeding programme because the level of inbreeding that is generally unacceptable may be deemed acceptable if it arises from relationship to the outstanding foundation animal. To advertise a linebred animal, the “outstanding” foundation animal should also be identified. Irrespective of the breeding strategy that is used, it is important to accurately record pedigree data, especially in breeds with small numbers of animals. The Ankole breed in South Africa is an example of such a breed (Photo 1), where the number of cattle in South Africa is limited and it is therefore unavoidable that inbreeding will occur. In a breed like the Ankole in South Africa, inbreeding will be the result of the limited number of bulls available that are not related to the females. It is therefore important that Ankole, and breeders from other breeds with small numbers in South Africa, understand both inbreeding and linebreeding.