Agata and the Mice by Peyton Ellas – The Milk House

Agata drove along the flat scrub of the west valley. Clouds a marvel of grey, gold, and pink. She pulled her third ham sandwich of the day out of the cooler. The late afternoon light made the frost-killed saltbush shine golden against the orange-tan soil.

At night, the mice in the walls kept her awake. The house was a rental. Temporary. She didn’t care about the mice but she wished they would let her sleep. She set the live trap in case the mice got into the cupboards. She put in foam earplugs she had stolen from work.

A month ago and thousands of miles east, Vasili had gotten rid of the dog but he wouldn’t say what he had done with him and after a week of searching in secret, Agata gave up. She found the dog’s bed, food, and toys in the trash bin. She left while Vasili was at work. Putting the clothes she didn’t want in the trash bin with the dog’s stuff. She took Vasili’s leather jacket. She hated it, but he loved it. She didn’t completely empty their bank account. Vasili was probably telling people he kicked her out. She pawned his jacket outside of Abilene and kept driving west. Like most people, he was smaller than Agata. He was like a lot of small men. Tried to make her the small one. Was mean to the dog. She would believe the dog had found better humans to live with.

In this new place almost to the ocean, Agata thought she would stay alone for a while. With the mice.

Agata had gotten a job driving a box truck, delivering trees. She had the proper licenses, a good driving record, and she was strong. Maybe she would get another dog. She was pretty sure Jim, the nursery owner, would let her keep it in the cab with her on long drives. He was the other type of small man, the kind that pretended to like it when Agata was bossy, pretended to like that she was larger than he. But the truth always came out eventually, often in sneaky or petty ways. So she hadn’t gotten a new dog yet. Her landlord was an old man who didn’t care about anything as long as Agata paid her rent. The house was a shack with termites besides the mice and sat way out on the salt scrub with no fence and no neighboring houses and only one small tree that looked to Agata like it appreciated that she was there. She left a hose dribbling water on it when she went to work and turned the water off when she came home, as if it needed routine care, as if it were like a dog in some small way.

This day, her last job for the day was at a new retail plaza in Arvin. The sky had a trace of light. The foreman strode forward, standing too close to the truck, not smiling, hands on hips. As she climbed down from the truck, she watched his face as he registered her size. No way was he going to mess with her. When she had been in elementary school, little kids hovered nearby so they wouldn’t get beaten up. She never fought anyone. When those little kids grew, they stopped hanging out with her. She didn’t blame them. She knew her personality was dull.

“Sorry,” she said to the foreman. “I know it’s late.”

“Yeah,” he said. Agata thought he’d probably take it out on some poor worker, or on his wife and kid or the family dog, and she was sorry for that. Jim gave her more work than she could do. Sometimes she delivered the last trees after dark and ended up sleeping in the cab on the side of the road or in a Walmart parking lot. But tonight, after unloading the trees with the forklift and getting the foreman’s signature, she returned the truck to the nursery and drove home in her dented but still running Camry. She ate a few cans of soup for dinner and made sandwiches for the next day.

She put the foam earplugs in so she wouldn’t hear the mice and almost didn’t wake up the next morning when her alarm went off. Drove faster than she liked to and only halfway in realized she hadn’t turned the water on for the tree. The sun slanted golden across the nursery yard. Pedro came out to help load the trees. They didn’t speak because Pedro only knew Spanish. Pedro was Agata-sized. She had seen him throw rocks at the nursery cats. Agata refused to learn Spanish.

Her first delivery was ten boxed Sycamores to a farm-animal rescue near Old River. She stopped the truck in the dirt parking lot, billowing clouds of dust off her wheels. Surrounding her were pipe corrals containing horses, mules, donkeys, a few cattle and one pen of sheep. Behind the pens, Agata saw pastures with horses grazing. She rolled down the window. She didn’t see any people. Jim told her to honk if no one was waiting, but she didn’t honk. She watched the animals surrounding her on every side except the road she had come in on. The clouds from yesterday had gone east, leaving a hazy blue sky. She thought about eating one of her sandwiches. Her body wanted food all the time. A big black fly buzzed lazily into her cab.

“Hoy!” A woman shouted. “The trees are here!” A bone-skinny woman carrying a shovel ran from a shed towards the truck, her loose, long, blond hair swinging back and forth.

“You brought the trees!” the woman shouted.

Agata didn’t bother answering, regretting not being able to eat the sandwich first, but climbing down from the cab. Another woman rode up in a golf cart. She was larger than the blonde woman, dark haired and brown-skinned. But not dark like Pedro. Maybe Italian or Arab. Or maybe just light-skinned Mexican.

“I’m Freida, the owner,” the dark woman said. To the blonde woman she said, “Shona, radio the boys and get them over here.” Shona pulled a walkie-talkie off her belt as she walked away, still carrying the shovel in the other hand.

“The county’s been all over me to plant something as a screen between me and the new subdivision. It’s like they think trees are gonna keep the flies off their sunning-by-the-swimming pool asses.” Freida laughed. “It ain’t like I wasn’t here first. It ain’t like I didn’t grow up here, inherited this plot that don’t grow fancy nut trees or citrus or even cotton. It ain’t like I am just out here trying to mind my own business and make a decent living working hard saving lives.”

“Sycamore trees aren’t going to catch flies,” Agata said. “But they’ll grow quick.”

“I know, I know,” Freida said. “I’ve always liked them.”

“They drop a lot of leaves,” Agata said.

“I know, I know,” Freida said. “Lots of big leaves for the neighbors’ swimming pools.” Freida laughed again.

Shona came back riding in an ATV driven by a medium-sized man with a wrinkled permanently sunburnt face. A skinny boy of about nineteen rode in the back. He hopped out before the quad was fully stopped, trotted to the tractor, jumped on the seat, and had the engine turned over and on before the middle-aged man was out of the ATV.

Agata watched this while lowering the forklift and opening the truck door. She climbed slowly onto the forklift seat, shifting around to get properly balanced. Seats were always too small for her.

She set the trees where Freida and the middle-aged man directed her. The boy was already digging holes with the tractor. Shona trotted around them with her shovel. Occasionally, over the forklift’s motor, Agata heard a whinny, or a donkey bray or a cow bellow. It made her think of when her parents took her and her younger sister to a petting zoo. The sheep and goats were frightened of Agata, and her parents had taken her out of the pen so her sister and the other normally sized children could feed the animals out of their tiny hands.

Once the trees were unloaded and placed, Agata loaded the forklift back on the truck. The skinny boy and the middle-aged man had already gotten half of the trees planted.

“Come and meet some of the animals,” Freida said. Agata was going to wave Freida off, but a horse snickered and Agata changed her mind. They went into the pen with baby donkeys. The donkeys ran up to both women and pressed against Agata’s large thighs.

“A natural!” Freida said. “Donkeys are good judges of character. They have decided you are okay.”

The skinny boy came up to the fence. “I’ve got the trees watered in. We’re going to set up an automatic system for them, yeah?” The donkeys ran over to him.

“The donkeys love Polecock,” Freida said. The boy was scratching their chins and grinning. Shona joined them, riding up in the ATV, stirring up dust, a porcelain plate of cookies on the seat next to her.

“Barky’s got lunch on,” Shona said.

Freida looked at Agata. “You staying?” Shona nodded enthusiastically, as if she were a child instead of a grown adult woman. Polecock grinning, scratching the donkeys’ chins with both hands.

Agata looked at the three of them, trying to see the joke. “I gotta go,” she said. “Truck full of trees.”

Their faces fell. Agata saw a resemblance. “Are you all related?”

“We didn’t used to be,” Freida said looking at Shona, then at Polecock.

“We’ve adopted each other,” Shona added. “We all found ourselves here out in the middle of nowhere, and now we’re like family.”

“Are family,” Freida corrected, putting her arm around Shona’s shoulders.

“Take these for the road,” Shona told Agata, holding out the plate of cookies. “Barky said so.”

Agata walked back to her truck, feeling eyes on her back. People often avoided looking at her frontside and then gawked backside. She had seen plenty of that in window reflections and catching people by turning suddenly.

On the road again, Agata glanced at the plate of cookies on the seat beside her. She would save them for later that night at home. She pulled out a sandwich from her cooler instead.

It was dark when Agata parked the truck in the nursery yard and headed towards her car. She had thought of the animal rescue place the rest of the day, bits and pieces of those strange happy people and of the happy animals floating in and out as she unloaded trees, rolled down the rural roads, bumped over potholes and came to complete stops at signs even when she could see no cars around from horizon to horizon.

She forced her arm through the ice chest handle so she could carry the plate of cookies in her hand, and her backpack and keys in the other arm/hand combination. She trudged across the yard with the security lights from the retail nursery casting a dim yellow light. Jim appeared in front of her, coming out of the dark. Agata stopped. They were both standing in the cast light, half shadowed.

“I bought you dinner,” Jim said. “It’s Taco night at Filipe’s. Beer too.” He sounded like he already drank a few. “It’s Friday night, let’s party.”

“I wanna get home,” Agata said.

“Ah, come on,” Jim whined, stepping closer. “I went to the trouble of getting you dinner. Least you can do is eat it.” The weight of the ice chest hurt her arm. She felt encumbered, awkward, with her belongings draped over her. Agata shook her head.

“You brought me cookies,” Jim said, taking one off the plate. “Did you bake these?” Agata shook her head.

“Delivery tip, huh?” He shoved a cookie in his mouth. “Pretty good,” he said between chews. “No one brings me cookies, even though I’m the one growing the trees.” Jim ate another one. With the ice chest on her arm Agata couldn’t move the plate away easily. Jim shoved a cookie in his mouth while sliding another few off the plate. There was only one left. The porcelain plate was patterned with swirls of blue, pink, and gold.

“Thanks anyway,” Agata said, and started trudging towards her car. If Jim was looking at her backside, she didn’t care. If he touched her, she would hit him in the head with the ice chest. She hadn’t driven all this way, across half the country, to get back into another mess.

“Tomorrow!” Jim shouted. Agata didn’t look back, shoved her stuff in the car and closed the door. Tears fogged her eyes. She was tired. But if a mouse was in the live trap, she would take it to the far pasture and release it before she took a shower and had her own dinner.

The live trap was empty. She heard the mice scrabbling in the walls but it didn’t bother her. Let them eat the wires in the walls. Let the termites eat the whole house. She ate her last cookie. The porcelain plate with its patterns of colors sat on the bed stand. She should return it. It wasn’t like it was a paper plate meant to be discarded.

When Agata got up it was dark outside. A sliver of gray showed in the east as she got in her car. She hadn’t packed a lunch. She chewed on bagels as she drove.

It was still early, the sun barely rising over the long flat horizon, when she arrived at the rescue. She had time to return the plate and get to work only a little late. Maybe Pedro would have her truck loaded when she arrived. He sometimes did that.

She parked the car near the sycamores. They looked good, healthy. Sprinklers on.

Freida, Shona, Polecock and the middle-aged man were all feeding animals or cleaning the pens. When Agata got out of the car, Freida waved, came over.

“Barky thought you’d be back,” Freida said. Agata held out the plate. Freida laughed. “You’d better take it to the house yourself.” She motioned with her head up the drive.

The house was a rambling ranch style, white with blue trim. Large oak, sycamore and elm trees draped their branches over it. A scraggly lawn tried to grow in the shade. There was a sprinkler going on the end of a snaking hose. The screen door was old-fashioned, wooden, the kind that banged. She didn’t see a doorbell, so she knocked on the door frame. She heard old time gospel music coming from the house. Agata thought these people might be in her mind. Too homey perfect. Too weird to be true. But if they were, she didn’t care. It felt good to be here. Safe. She didn’t feel stared at, which never happened, ever, since she was a child, the biggest child in the classroom, always.

“Hey, there.” A woman’s voice startled Agata. The voice had the sleepy southern accent Agata had gotten used to hearing in this part of California. One of the young girl workers at the nursery had told Agata that a lot of people were descended from Oakies and Arkies that migrated during the dust bowl days. Those accents got mixed up with the more recent accents from Mexico and Central America and the kids now had their own way of talking that made them sound different than those who grew up along the coast. Agata had worked hard to lose her accent, and she wondered now if she would sound different to those back where she had come from. Had she picked up some of the Oakie that this woman’s voice carried?

The woman was coming around the side of the house. She was not small, but not as large as Agata (who was?) and much older, with gray hair. Agata held out the plate.

“Brought my plate back. That’s real nice of you. Not expected, but real nice. I’ll get it filled up again for you in no time.” She reached around Agata and opened the screen door.

“Come on in. I’m making breakfast. You might as well stay if you can spare the time.” Agata followed the woman in the house.

“Are you Barky?” Agata asked as they reached the large farmhouse kitchen. The room was painted bright yellow, a large oak table plop in the center. The countertops were old white tile, and everything gleamed clean with shiny chrome fixtures.

“Yep,” the woman said, now turning back to Agata, with an open smiling face. She tied an apron around her large middle, straining a little to reach behind herself.

“Agata.”

“You can set the plate in the sink if you would,” Barky said, leaning into the open refrigerator. “You know how to cook?”

Agata shrugged. “I guess.”

“That’s what I always say, too. But they keep on eating what I fix so I guess I cook good enough.” Barky turned her head a little to see Agata’s reaction. Agata smiled. It was the first time she’d done that in weeks, since she had seen a puppy playing with a kitten at one of her deliveries.

Agata had to ask Barky what to do with some of the food. It wasn’t until halfway through frying up peppers and onions with a block of tofu mashed into it that Agata realized all these rescue people must be vegans. They looked healthy enough, but she decided she’d stick to the store-bought hash browns Barky put in the oven to cook. Barky squeezed oranges into a pitcher and set the table.

Agata’s phone buzzed. The nursery. Would it be Angela, the office manager? Or Jim? She didn’t answer.

Barky handed six plates of food to Agata to put on the table. The four crew members filed in as on cue. They smelled of manure, straw, and dust. Freida and Shona went down the hall. Polecock sat down at the table.

“Did you meet Elio?” Barky said, motioning with her head towards the middle-aged man washing his hands at the kitchen sink.

“Sort of,” Agata said. Elio turned and grinned, wiping his hands on a bright white kitchen towel. He was missing a front tooth. Freida and Shona came into the kitchen and sat at the table. Agata sat next to Shona. It didn’t look like they had to squeeze her in, the table was big enough for her to have plenty of space. She sat gently on the old wooden chair at first and then settled in as she realized it was strong enough to hold her weight.

The five of them talked about animals: which ones were doing well, which ones had adoption applications on them, when the veterinarian would come again. Shona and Polecock were heading out later to pick up two horses the owner was surrendering. Agata tried the mashed tofu and decided it was not horrible, especially with ketchup. But she still preferred the hash browns. And everything could be washed down with Barky’s strong coffee. At the nursery, Jim penny-pinched by having Angela make the coffee weak and pretending to run out of sugar and creamer. Once, Jim had teased Agata that she drank more coffee than the rest of the crew combined.

“I guess that makes sense, you being the largest,” Jim had said. After that, Agata was careful to only drink one cup in the mornings. Agata thought about this as Barky refilled her cup and everyone else’s except Shona’s, another routine, like the hand-washing, Agata imagined them doing over hundreds of breakfasts.

Barky got up and started packing snacks in a big cooler, the kind Agata had.

“Can’t we get the horses tomorrow?” Polecock asked.

“I know you hate to drive,” Freida said, “But you’re better at it than the rest of us.”

“Punishment for being good at something,” Shona said. “I don’t even have a license.”

“You mean I gotta get in a wreck or something to get out of it?” Polecock asked.

“Don’t you dare,” Freida said. They were all laughing, except Polecock. He didn’t seem the type to intentionally wreck, but who really knew what someone would do? Agata had never thought Vasili would end up being a creep and getting rid of her dog.

“I’ll drive,” Agata said. They all looked at her. “If you want me to.”

“Thank you!” Polecock said, lifting his chin like he was saying it to the ceiling. “I like horses. I like the trailer. I’m fine with hard work and pig shit. But I do not like to drive.” They all looked at Freida. She shrugged.

“Fine.”

The drive was no problem for Agata. Shona and Polecock talked to the owner and then loaded the horses into the trailer while Agata hung out next to the truck. When they were ready, all three got back in and Agata started the engine. Polecat sat in the back of the club cab and Shona rode shotgun.

“I guess horses might be a bit like trees,” Shona said. “Just don’t knock ‘em over with wild driving.”

“Okay,” Agata said. She hadn’t towed a trailer all that much, but it wasn’t anything difficult. She took the curves easy, imagining the horses swaying in the trailer, frightened, not sure what had just happened, not sure what would happen next.

“You’re a good driver,” Shona said.

“Way better than me,” Polecock agreed, from his seat in the back cab.

Through the front window, Agata noticed how the wide flat valley seemed cut open by the two-laned road. Shona was digging into the cooler for the snacks. Clouds stretched from horizon to horizon, swirls of snowy white against the pale blue sky.

*

Learn more about Peyton on the Contributors’ page.

Learn more about Peyton on the Contributors’ page.

Peyton’s book, Gardening with California Native Plants: Inland, Foothill, and Central Valley Gardens, was published in 2018 and is available here.

(Photo: rulenumberone2/flickr.com/ CC BY 2.0)

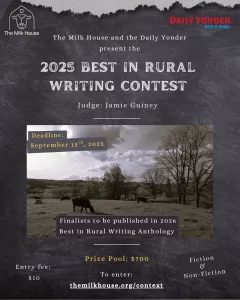

The 2025 Best in Rural Writing Contest is now underway!

$500 first prize, $200 runner-up. $10 entry fee. Finalists will be published in the 2026 Best in Rural Writing print anthology.

Accepting fiction and nonfiction under 7,000 words. To enter, click here.

Deadline: September 15th, 2025

The 2025 Best in Rural Writing Contest is sponsored by The Daily Yonder. The Daily Yonder offers news, analysis and stories from Rural America, free for readers to enjoy. Visit dailyyonder.com to get more great rural stories, or sign up to their newsletter to receive rural reporting directly in your inbox. Alternatively, you can listen and subscribe to their podcast, Rural Remix, wherever you get your podcasts.